Door, birds, fleece blankets, laser, drill, plastic: too generic to give away much, and too specific to be arbitrary, the material list for Michael E. Smith’s sculptures reads like a piece of concrete poetry. What the artist makes from these elements has a macabre wit, in turns tender and tragic, loaded and light. For his first solo exhibition in Switzerland, the artist works, as he always does, with unassuming, discarded things, resonant with the accumulated traces of their existence, and transformed through the simplest of gestures into captivating, uncannily sentient-seeming sculptures.

Even before you enter the exhibition, you notice two individual-seater sofas that bear traces of the lives lived with them—drink spills, sweat stains, scratches from having moved house. They are positioned at a precarious angle in relation to the grand stairway, defying gravity as they resist sliding down the stairs while seeming to carry on a ghostly conversation. On the landing in front of the entrance to the exhibition hangs the rem- nants of a hollow-core basement door, some- what chipped and marred from use, cut into two curved parts, each adorned with a taxidermied bird stiffened in resin (a pigeon on one side, a chicken on the other). Mute and motionless, they slyly echo the angel’s wings in the historic mural nearby, underscoring how Smith’s works can be simultaneously disquieting, heartbreaking, and laced with humor.

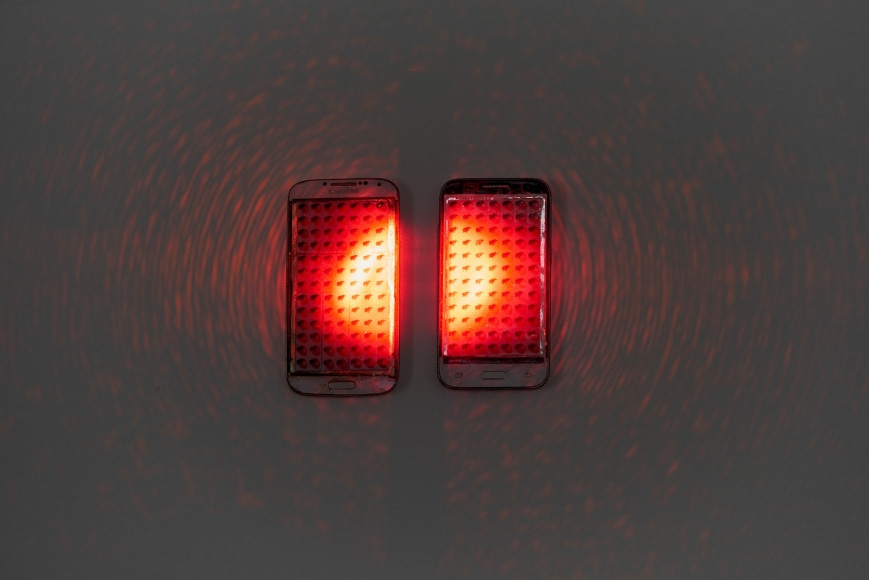

In the exhibition space proper, used fleece robes and blankets in gradients of white and cream hang on a high metal railing. To see the shabby, formless pile is to imagine the bodies that the garments once covered, the bodies that once dirtied them, and even—given the disastrous eco- logical impact of the cheap synthetic material— the bodies that are slowly but inevitably ingesting them as their microfibers enter our water, soil, and food streams. Below, a laser pointer beams its focused red light across the room onto a metal pole fitted into a drill head, the sort used to dig wells or extract oil. Part animistic totem, part futuristic robot, part stripped-down industrial version of Alberto Giacometti’s 1960 L’Homme qui marche, the sculpture is about the size of a tall person, the glowing point of light giving it eerie life (or acting as an unsettling threat, since the dot recalls the beam of a firearm laser sight). The light continues past the upright object to the space behind, precisely hitting two altered and wall-mounted cell phones that make the light projected on them feel like technoid em- bers, their screens replaced with tabs of LSD— homemade psychedelic smartphone “apps.”

Another object, dangling in the threshold to the last room, is made from the legs of a heron attached, marionette-style, to a roll of plastic wrap with a rubber handle so that the bird’s stiff limbs sway with the slightest draft. The contraption is positioned just above a floorboard plank that the artist removed to reveal the institution’s electrical channels and infrastructure. Given that the resultant crevice is almost exactly the same length as the surreal handle-plastic-legs-thing, were it to be laid horizontal, you can’t help wonder if it is a makeshift grave for the bird sculpture. Finally, on a wall near the exhibition’s entrance door, perhaps most noticeable on your way out of the show, a child’s sweatpants, one side plumped thanks to the addition of an unseen ball, appears lonesome, hung at about kid height.

Factually, materially, these are the elements in Smith’s sparse but pregnant exhibition of untitled sculptures. The combinations are distinctly simple, and as odd and as typical as any in Smith’s oeuvre. Here, as he so often does, the artist gives a second life to debris, animal corpses, clothes, used furniture, and things whose original function was to provide some sort of elemental protection. Cut, smashed, piled, drenched in resin, illuminated with a laser beam, or touched in some other way, his amalga- mations never quite hide the former function of their components. Nor is there fancy suturing or high-production gloss between or around them. They are what they seem to be. Yet this hardly begins to convey their deeply haunting effects. In the sweatpants work alone, your mind races to imagine the child who would wear the sports apparel, leg swollen with injury or disease, or somehow stunted from playing ball. Or how two sofas face to face could conjure up individuals unable to communicate. “One can’t walk, the other can’t talk,” the artist himself artlessly noted. Yet his resultant art- works touch you, trouble you—indeed, work on you.

Throughout, a cold, bluish light gives everything a dismal tinge, rather than the warm sunlit glow typical of the space. This modification of the lighting, in other words, of the very ambi- ance of your experience, is not unusual for the artist, and is of a piece with the artworks in the show. Each object seems paradoxically both deeply appropriate and totally out of place. The former because they speak of the indignity of our contemporary moment—a world suffering from ecological, social, and economic meltdown—and the latter because they are so humble in scale, so against the majesty of the space they occupy. They seem off, wrong per- haps, even as, in their unpretentious strange- ness, they ineffably command the space itself. A last work, comprised of the outer hairy skin of four bull testicles cut and arranged in an X, is installed in the staff office. This unusual place- ment of an artwork outside the space of the exhibition but conceptually part of it, uniquely available to the institution’s personnel, suggests how questions of labor and the laborer under- gird Smith’s practice.

The artist’s native Detroit is a city devastated by globalization and the decline of industry in the United States. And one senses that it is from there that Smith channels some “ghosts” (as he once called them) as he makes his decidedly human-scale works. These objects are not born of compositional strategy, or formal flourish, but something that might best be called affec- tive resonance. Although they engage sculp- ture’s primary questions of gravity and weight, they feel less “sculptural” in a classic sense, and more like things removed, misplaced, ren- dered at once disquietingly familiar and strange through meetings with other elements (or sometimes just a new habitat). In a world where so much is seamless and gleaming, all in the service of making it more immediately covet- able, transactable, and instagrammable, Smith’s objects don’t resolve themselves in any tidy manner. Their alien life forms instead demand slowness, attention, self-questioning.

The heart of the exhibition is not a set of discrete if strange artifacts, but rather the universe that intangibly connects them, with the empty blankness that surrounds them acting as part of the artworks themselves. But as the artist himself is quick to point out, if a certain sparseness con- sistently characterizes his practice, the endgame is “less Donald Judd than a lobotomy”—in other words, not emptiness refined into chic minimalism, but emptiness as evisceration, which speaks with urgency about loneliness, the hu- man condition, and the dystopia of our present moment. Yet however pathos-filled, the out- come is not unequivocally bleak. It is at mo- ments absurdly funny too, and maybe therein lays its promise of hope. Like the symbol that the artist chose to spread across Basel to enigmatically represent his show, he proposes, in place of an exhibition poster or title, not a word but a sound—a sound to clear out negative energy, to enable a restart.

(Source)