Born in 1986 in the suburbs of Paris, Julien Creuzet is a French artist whose work is heavily influenced by his upbringing in Martinique. Raised on the Caribbean island at the intersection of diverse cultures, his practice reflects the region’s fusion of African, indigenous, and European traditions. His often expansive installations, which encompass sculptures, image displays, sound and video works, are strongly influenced by his biography and cultural background;

he frequently incorporates found objects and culturally coded everyday objects into his work. At the same time, his practice also points beyond his personal experiences to reflect the collective social realities of the Caribbean diaspora. Creuzet pays close attention to the problematic interface between Caribbean history and European modernity. Visual and acoustic idioms converge, move, and transform in his installations, undergoing a process of creolization. They enter into a dialogue with themes of emancipation, the spirit of Black self-assertion, and the artist’s own diasporic experience. Creuzet’s work interacts with viewers on a poetic, sensory, and emotional level, inviting them to question their own cultural assumptions, privileges, and codes.

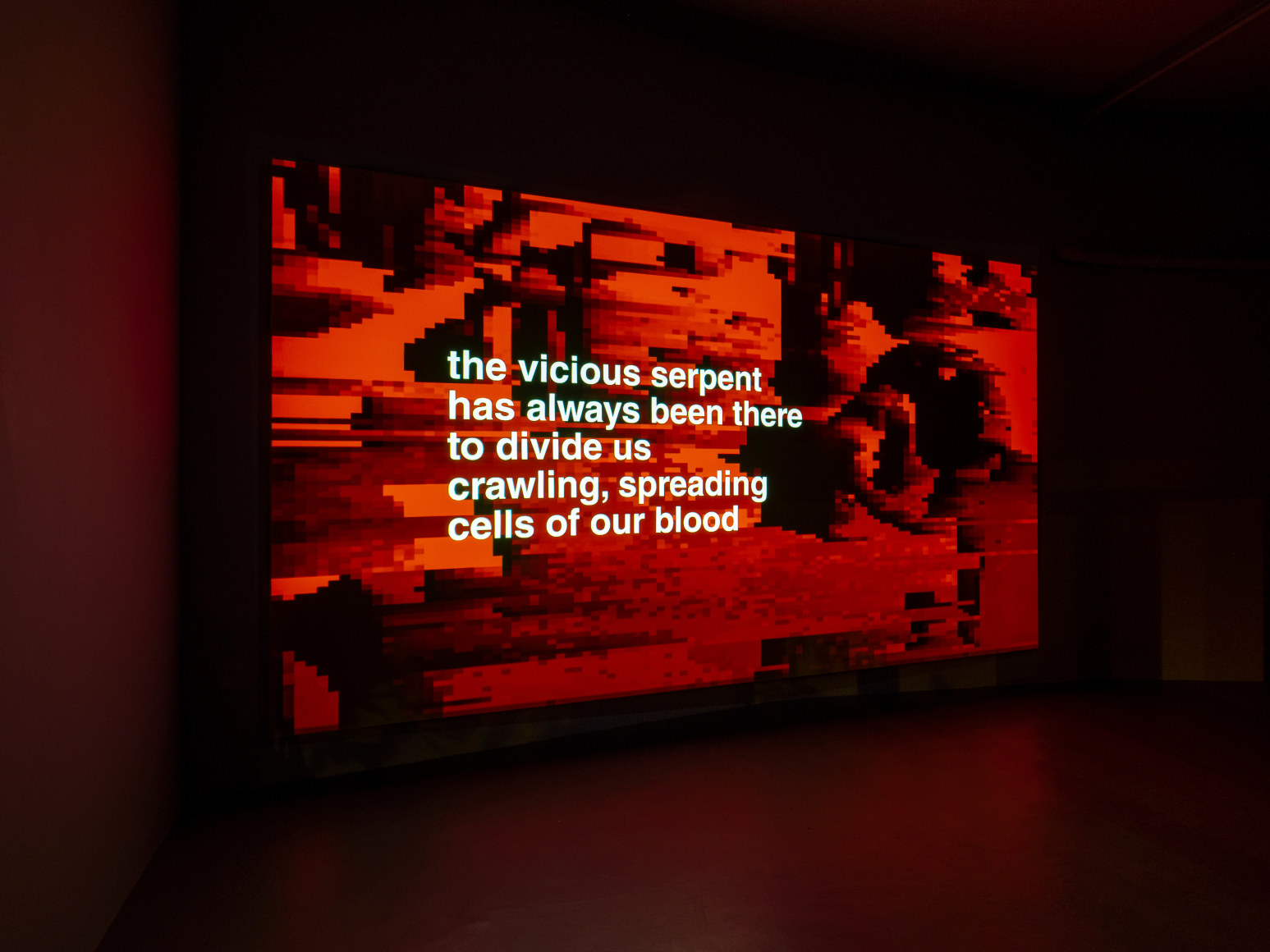

Assidule, 2019, is a hypnotic video work that interprets and depicts the collision of encounters as contagion. 3D objects resembling gold tokens or coins travel through a cavernous living artery, crossing paths with a knife, the French national flag, and a ship loaded with stacked cargo containers. What follows are high-contrast, at times surreal and whimsical visual landscapes: a black, infinite universe with unfamiliar objects swirling; bananas twitching and spitting out colorful pills; a glitchy, heavily pixelated red-and-black dance scene with dancers highly distorted, their movements accompanied by lines of text; pulsating banana trees in an evergreen banana palm tree forest; animated male and female reproductive organs swirling as airplanes circle around them. The visual impressions evoke a wide range of associations, recalling educational science films, 1990s music videos, surreal dream sequences, or fantastical computer game landscapes. They also defy rational classification, resulting in an open and opaque (narrative) space that generates its own unique emotions and memories.

Julien Creuzet’s poetic meditations on racialized corporeality take us on a mesmerizing journey through a dynamic visual landscape, accompanied by a soundtrack that underscores the artist’s African heritage. Lyrics heard in the song double as the title of a sculpture that was created simultaneously with the animated video shown here: Mon corps, carcasse, se casse casse casse / Mon corps canne à sucre flèche flèche flèche / Mon corps banane est en larme larme larme / Mon corps peau noire, au coucher du soleil, / ne trouve le sommeil / Mon corps plantation poison / Mon corps plantation poison / Mon corps plantation / Demande la rançon / La pluie n’est plus la pluie / La pluie goutte aiguille / La pluie acide pesticide / La pluie infanticide / Mon père vivait près de la rivière / La rivière était à la lisière / Du champ de banane pour panam / Banane rouge poudrière / Sous les tropiques du Cancer, 2019.¹ The lyrics were written specifically for the piece and are accompanied by a dynamic, lively Afro-pop soundtrack referencing the musical cultures of the Caribbean, where joy and sorrow intermingle. At the same time, the song’s lyrics also convey a checkered history with specific allusions to a real-life environmental disaster in Martinique and Guadeloupe: From 1972 to 1993, the pesticide chlordecone was used to combat a banana pest. This resulted in the contamination of soil, rivers, and groundwater, with serious health- and environmental consequences for the local population.

Woven into Assidule are a number of themes and references that reoccur throughout Creuzet’s work. The artist emphasizes, for instance, the positive and creative potential of creolization, a term that refers to the process by which elements of different cultures are blended together to create something new. He frequently references Édouard Glissant (1928–2011), a Caribbean-born writer and cultural philosopher whose work is widely recognized as a touchstone of postcolonial identity and cultural theory. As Creuzet himself notes, “I prefer the term ‘creolization.’ It is much more appropriate because it reflects the meeting of different cultures and how cultural encounters can generate new things rather than consume them, like in the historically demonstrated relationship of settler colonialism. Creolization, for me, is based on an understanding of positioning the body as a contact point in constructing experiential agency and self-determination.”² The video presented here similarly reflects the artist’s approach of merging visual and sonic landscapes, as well as the materiality of elements from diverse cultures, with the aim of producing “images of encounters, improbable images” that stimulate the imagination. His convinced that even “a container, a flag, and a machete inside a cave tells you a lot of things. It is important for me not to reduce the interpretative part of each element. Contextualizing creolization as contagion gives latitude to the complexity and parameters of being, especially for those familiar with being shipped and surveilled.”³ The processes of cultural blending, identities, and narratives described here are often not part of the biographies of viewers socialized in Western cultures, and consequently cannot be fully understood through their own horizons of experience. This makes it all the more important for artists from the Global South to offer their point of view, thereby facilitating the change of perspective that is so urgently needed to counter the cultural dominance of the West.

Julien Creuzet’s artistic practice is also significantly defined by the process of poetization, which he describes as follows: “It goes back to the same reason I privilege the poetic format of my titles: poetry offers the opportunity to utilize another voice. The multitude of forms and materials create this breathing space, without which art has no meaning. It also offers me the chance to resist the constant tendency to explain what I’m doing, how I’m doing, or who I’m doing this for, and lean more toward the liberatory aspects of imagination, play, form, and feeling.”⁴ To explore Creuzet’s visual realms is to encounter a realm of possibility, to become involved in the emergence of novel narratives and spaces that broaden one’s horizons of perception and experience.

Julien Creuzet (b. 1986, Le Blanc-Mesnil, France) currently lives and works in Paris. He studied at the École supérieure d’arts et médias de Caen/Cherbourg, completed postgraduate studies in fine arts at the École nationale supérieurre des beaux-arts de Lyon and at Le Fresnoy – Studio national des arts contemporains. Recent solo exhibitions include those at LUMA Arles (2022); Camden Art Centre, London (2022); Centre Pompidou (for the Prix Marcel Duchamp), Paris (2021); Document, Chicago (2021); Palais de Tokyo, Paris (2019); CAN Centre d’art Neuchâtel, Switzerland (2019); and Fondation d’entreprise Pernod Ricard, Paris (2018). His work has featured in numerous group exhibitions and biennials, including presentations at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (2022); Museum Tinguely, Basel (2022); KAI10, Düsseldorf (2021); SAVVY Contemporary, Berlin (2021); WIELS centre d’art contemporain, Brussels (2021); Manifesta 13, Marseille (2020); Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt am Main (2020), Kampala Biennale, Uganda (2018), and the 12th Gwangju Biennal, South Korea (2018).