Like many women artists of her generation, Barbara T. Smith (born in 1931) has been waiting a long time to finally have what the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, calls “The Year of Barbara.” As Director Anne Ellegood outlines in her introduction to the exhibition catalogue Proof, 2023 has brought Smith a small solo exhibition at the Getty Research Institute celebrating her archive there and an accompanying published memoir. Building off this, Proof represents—at last—a full career retrospective. The exhibition opened at ICA LA at the end of 2023 and traveled to Brown Arts Institute, where it was on view until June 2. It included the full range of her artist production: dozens of artists’ books and xerox drawings (including her “Coffin” books), performance notes, installations, and video and photographic documentation of her bodily and food-related performances. When it comes to the connection between publishing and performance, Smith is on the list of greats (which includes Alison Knowles and Carolee Schneemann). With Smith’s work, performance is publishing and publishing is performance.

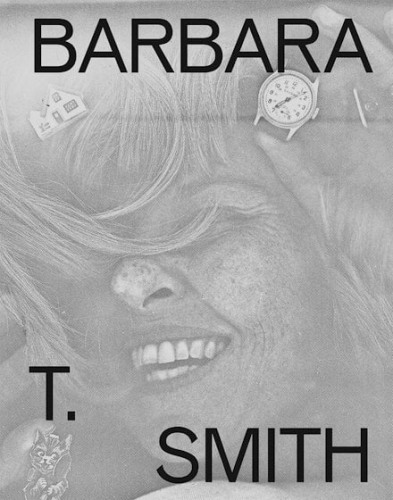

It is not an easy task to document and anthologize performance art in a monograph, especially performances so attuned to published forms. Proof, published with the support of Gregory R. Miller & Co and expertly designed by Content Object, finds a way. The lightweight softcover, just over 150 pages, smartly suggests its breath of contents with the front and back cover illustrations. The front features Smith’s smiling young face in black-and-white pushed up against the surface, a xerox print from the mid-sixties when she was first awakening as an artist, experimenting with her body and the potential of printing. The back cover features another experiment with printing her body, this time a brightly colored 2016 print of her hands (now featuring a few more wrinkles) pressed against the glass of a scanner bed. Thus we see the bookends of the book as her earliest and more recent experiments with the performance of publishing her body. As Gloria Sutton writes in her essay, “Fifty years after she made her first Xerox prints, Smith is still producing works that, despite the variations and repeated operations, continue to bring us closer to the inimitable trace of the artist herself.” So much of Smith’s performance work was seen as radical—her Xerox books radically displaying her naked body and genitals; her food performances radically changing our ideas of consumption; and her performances with others that incorporated sexual content. Her 2016 scanner experiments are in a way still as radical, as the aging female body is often also treated as a taboo subject.

The book is jammed with information and images, yet the design is airy. The chronology that runs throughout keeps us grounded (a tactic used by the same designer in another ephemera heavy book, the exhibition catalogue for MoMA’s Just Above Midtown show). It covers the full expanse of her career through last year’s published memoir, with details of various performances and the performances and excerpts of her own writings about these works quoted throughout. For example, in 1969 Smith created one of her first major performance events, Ritual Meal. “My guests came to consume the corpse to the intense tune of a cosmic heartbeat. For six hours they fed, course after course, served in surgical vessels,” Smith says of the piece in the chronology.